L.A. Art Show 2023 — exhibiting my work with bG Gallery.

In my opinion, galleries are collapsing under the weight of their own inefficiencies and conflicts of interest. The economics alone are absurd. Galleries routinely take a 50% cut of every sale; a markup no other industry would survive, thereby leaving artists with a fraction of the value they create. And buyers, ironically, become the victims of this inefficiency: they pay premium prices inflated not by artistic merit, but by an outdated distribution system.

Now, if that weren’t enough, a tiny, arcane circle of galleries decides who the “cool kids” are. A handful of power brokers anoints the chosen few, shapes museum programming, and manufactures cultural legitimacy. Everyone else, artists, collectors, and even institutions, is downstream of their decisions. But if anyone deserves to be closest to the source, it’s the people actually buying the art.”

The efficiencies extend far beyond simple communication. Commissions are dramatically better in this emerging model, with artists retaining far more of the value they create. Museum curators are freer as well — able to champion the work they believe in without worrying about alienating a museum director who answers to a mega-gallery donor. And consultants handle the tasks galleries once monopolized: they help collectors build thoughtful, balanced portfolios for clear, transparent, nominal fees. No hidden markup. No political pressure. No gatekeeping.

If I were responsible for moving human culture forward — if it were my job to decide which works deserve to enter the fine art canon — these are the criteria I would use: Originality, Contribution, and Continuity (OCC) as my benchmark... I picked a handful of well-renowned artists below to illustrate how Originality, Contribution, and Continuity can be a valid way to judge museum-grade work.

Claude Monet:

Originality: Monet did not paint water lilies; he painted the physics of perception. His originality was not in inventing Impressionism outright, but in pushing it past experiment and into clarity — revealing how light, color, and atmosphere become experience inside the eye. He dismantled academic realism and replaced it with a new visual truth: the moment as felt rather than the scene as recorded.

Contribution: Monet was not the first Impressionist, but he is the one who solidified Impressionism into a movement. With Impression, Sunrise, he transformed scattered innovations among artists into a coherent genre, a visual philosophy with momentum. He contributed more than technique; he contributed infrastructure — a shared aesthetic, a unified cause, and a cultural direction. Monet didn’t just paint the movement; he organized the gravitational center that made it unavoidable.

Continuity: Monet evolved relentlessly. From Argenteuil to the Rouen Cathedrals to the vast late Water Lilies, the thread is unmistakable: a single mind deepening a lifelong inquiry. This is continuity — not repetition but refinement, a disciplined devotion to understanding how humans perceive time and light. Monet stands as a blueprint for how an artist builds civilization: through patient, focused, enduring insight.

Georgia O’Keeffe

Originality: O’Keeffe did not paint flowers; she painted the architecture of attention. Her originality came from isolating form, stripping away the decorative, and revealing the monumental inside the intimate. Nobody before her had taken nature’s fragments — bones, blossoms, desert horizons — and transformed them into pure emotional geometry. She saw scale not as a measure of size, but as a measure of importance.

Contribution: O’Keeffe redefined American modernism by giving it a new visual grammar: clarity, distillation, and radical focus. While others looked to Europe for direction, she carved out a distinctly American visual identity rooted in light, space, and internal experience. She didn’t just contribute works; she contributed a new way of seeing — one where magnification becomes revelation and abstraction grows out of reality rather than escape from it.

Continuity: O’Keeffe’s evolution was unwavering. From the charcoal abstractions to the New York skylines to the New Mexico desert, the throughline is unmistakable: a lifelong search for the essential. She stayed disciplined, independent, and fiercely consistent in her pursuit of clarity. Her continuity was not stylistic stagnation but an unbroken deepening of vision — a sustained commitment that allowed her to shape an entire chapter of American art.

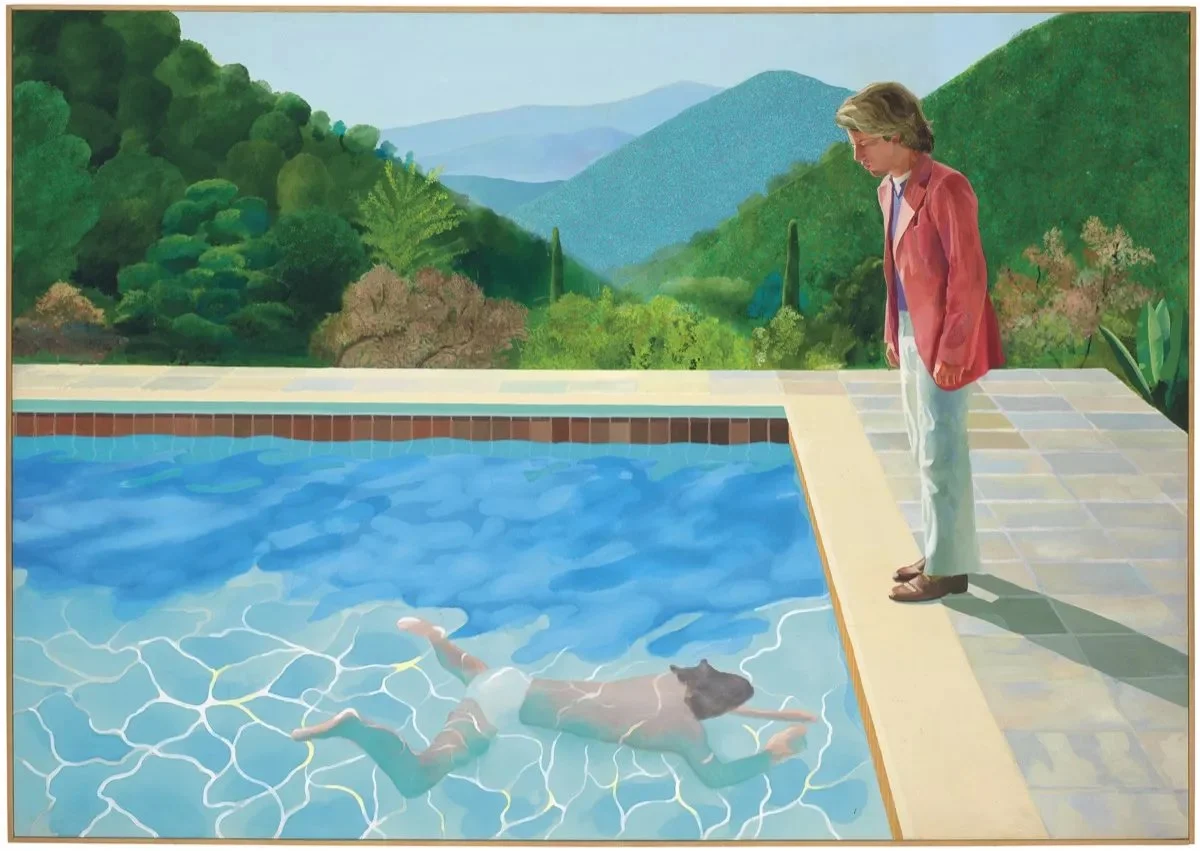

David Hockney:

Originality: Hockney’s originality lies in his persistent reinvention of vision. He questioned how we see — through perspective, memory, movement, and even screens. Whether in pools, portraits, photo collages, or iPad drawings, he explored the mechanics of looking with a curiosity bordering on scientific.

Contribution: Hockney embraced technology before it was fashionable. Photography, Xerox machines, Polaroids, faxed drawings, digital tablets — he treated each tool as a new brush, expanding the possibilities of contemporary painting. His contribution was to dissolve the boundary between medium and message, proving that innovation in tools can lead to innovation in perception.

Continuity: Though his styles shift, Hockney’s continuity is intellectual: a lifelong reinvention of how art captures experience. Every phase — swimming pools, Yorkshire landscapes, digital work — circles the same pursuit: How do we see the world, and how can art make that seeing more alive? His consistency is his refusal to stand still.

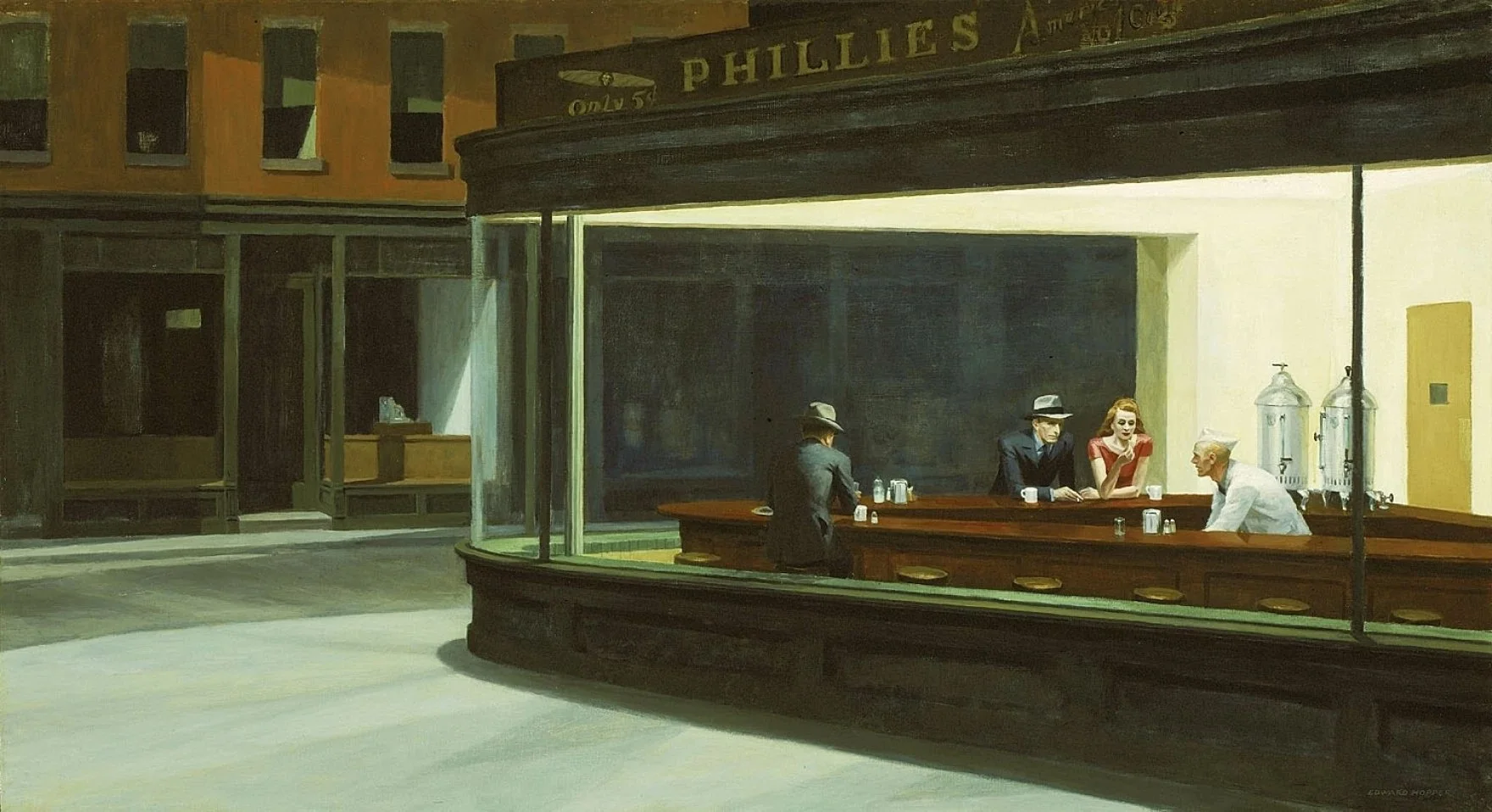

Edward Hopper

Originality: Hopper’s originality was his ability to turn isolation into a universal language. He distilled scenes into psychological states — a gas station at dusk, a woman by a window, a diner glowing in the dark — each one a quiet compression of longing and distance. He recognized that modern life was full even when nothing happened.

Contribution: Hopper contributed an atmospheric vocabulary that fused space with emotion. He redefined realism not as documentation but as mood. Through light, architecture, and silence, he created a cinematic grammar that influenced generations of filmmakers, photographers, and painters. Hopper showed that atmosphere can reveal humanity more deeply than narrative ever could.

Continuity: Hopper maintained a disciplined, lifelong exploration of solitude. From the early etchings to the final watercolors, the central inquiry never changed: How does space shape the human condition? His continuity is not monotony but mastery — a deepening of a single, resonant human truth.

Egon Schiele

Originality: Schiele’s originality lay in his line — raw, angular, electric. He stripped the body of idealization and revealed the nervous system beneath the skin. No artist before him exposed human vulnerability with such immediacy. His line was not just a tool; it was a psychological probe.

Contribution: Schiele contributed a radical new understanding of the psyche. His portraits were not likenesses but self-dissections — an unfiltered confrontation with desire, shame, alienation, and interior conflict. He forced viewers to witness the human mind laid bare, advancing the notion that art could reveal identity not as a mask but as a rupture.

Continuity: Despite his short life, Schiele’s continuity is unmistakable. Every period, early, mid, late — circles the same obsession: Who am I beneath the surface? Who are you when your defenses fall away? He deepened this inquiry relentlessly, refining it until line, psyche, and identity fused into a singular, unmistakable voice.

Andy Warhol

Originality: Warhol’s originality was not just that he painted soup cans; it was that he painted what everyone had in common. He saw the unspoken democracy of American consumption: the president drank Coca-Cola, and so did the factory worker. In a fractured society, he identified the cultural objects that unified people across class, geography, and status. His originality came from recognizing that the shared everyday object was the true icon.

Contribution: Warhol’s great contribution arrived by accident — an over-painted lip line on his Elizabeth Taylor silkscreen. That mistake transformed Taylor from a person into a construct, a symbol rather than an individual. Warhol realized in that moment that celebrities had replaced the ancient gods and goddesses: larger-than-life, endlessly reproduced, worshipped, consumed. He shifted art’s mission from depicting reality to revealing the machinery that manufactures reality — fame, commodification, myth.

Continuity: Across every phase of his career, Warhol returned to the same idea: American culture fabricates its own pantheon. From Marilyn to Mao to disaster series to Brillo Boxes, the throughline is unmistakable — a lifelong study of how icons are created, circulated, and adored. His continuity was not stylistic; it was anthropological. Warhol chronicled the birth of a new religion: the worship of the image itself.

Summation:

In the end, culture has always belonged to the people who care enough to build it — the artists who create the work and the collectors who give it a life beyond the studio. When a small circle of intermediaries controls the gate, culture shrinks. But when artists, consultants, and engaged collectors shape its direction, culture expands. It grows more diverse, more democratic, and more honest. The future of art will not be determined by a handful of galleries deciding who belongs; it will be shaped by those who recognize originality, reward contribution, and support continuity. That is how civilizations have always advanced — not through exclusivity, but through participation. The gatekeepers had their century. The next one belongs to all of us.