https://www.instagram.com/reel/DUkNVvOji_C/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link&igsh=MzRlODBiNWFlZA==

FRIEZE Magazine: Who Killed the Independent Curator? /

Everyone Is a Curator Now — And That’s the Real Problem

FRIEZE MAGAZINE: Who Killed the Independent Curator? Biennials have become a side-hustle for institutional directors, creating far-reaching consequences for the global art world: Link

The recent hand-wringing over the “death of the independent curator” feels oddly familiar. It echoes the advertising world of the 1980s, when desktop publishing and early digital tools sparked a panic summarized by a famous line: “Everyone is an art director now.”

That slogan wasn’t wrong—but it also wasn’t the real threat.

The real threat was not democratization. It was power concentrating upward while accountability thinned out.

Today’s art world is replaying that pattern almost verbatim. The anxiety isn’t really about independent curators disappearing. It’s about who gets to decide, who pays, and whose taste is protected from scrutiny.

The Cost Problem Nobody Wants to Name

Independent curators are expensive. Not just financially, but structurally.

They require:

Fees that don’t neatly fold into institutional payrolls

Autonomy that resists donor preferences

Time, travel, research, and risk

Freedom from internal hierarchies

Institutions increasingly don’t want that friction. It’s cheaper, safer, and more controllable to fold curatorial authority inward—toward salaried staff, directors, or consultants already embedded in existing power networks.

When critics describe this as the “brushing aside” of curators, that part is accurate. But the cause isn’t cultural decay—it’s institutional convenience.

Nepotism, Soft Power, and the Curatorial Echo Chamber

There’s an uncomfortable truth often left unsaid: curatorial culture can look nepotistic from the outside because, in practice, it often is.

Not always maliciously. More often through:

Repeated use of the same artists

Reliance on familiar networks

Social and educational homogeneity

Career circulation within elite circles

That’s how closed systems behave, even when intentions are good.

So when the phrase “everyone is a curator now” gets tossed around as an insult, it misses the point. The problem isn’t that too many people think curatorial thoughts. The problem is that too few decisions are exposed to open competition.

The Board of Directors Is the Real Curator

Here’s the part that makes everyone uncomfortable:

Ethics and politics in museums do not start with curators. They start with boards of directors and major donors.

Board of Directors:

Want their collections exhibited

Want reputational safety

Want alignment with their values and investments

Want predictability

That reality quietly shapes exhibitions long before any curatorial statement is written.

Blaming curators—or mourning their loss—without addressing governance is like arguing about set design while ignoring who owns the theater.

A Proposal That Would Change Everything

If institutions genuinely care about artistic merit, diversity of vision, and credibility, there’s a brutally simple experiment that would expose the truth:

Open-call curatorial bake-offs with anonymous submissions.

No names.

No résumés.

No gallery affiliations.

No social capital.

Just the work.

Curators would still curate—but from a pool where taste must stand on its own, not on proximity to power.

Yes, it would be messy.

Yes, it would offend some people.

Yes, it would break habits.

That’s the point.

Why This Threatens the “Cool Kids” Narrative

The mythology of the art world depends on scarcity of access, not scarcity of talent. Anonymous selection punctures that myth immediately.

If the best work rises without pedigree, then:

Gatekeeping loses its justification

Networks lose their camouflage

Boards lose plausible deniability

Curators regain legitimacy through judgment, not affiliation

That outcome should terrify anyone invested in exclusivity masquerading as rigor.

Not Anti-Curator. Not Anti-Institution. Pro-Art.

This isn’t an argument for abolishing curators or flattening institutions. It’s an argument for restoring credibility through competition and transparency.

Curators matter. Institutions matter. But neither should be protected from scrutiny by tradition alone.

If the art is strong, it will survive anonymity.

If the curatorial vision is strong, it will survive open process.

If the institution is ethical, it will survive losing control.

And if any of those can’t survive that test—then the problem was never democratization.

It was fragility.

Strategic Pause or surrounding the wagons? /

Art market insiders are calling it a "strategic pause." Let's call it what it is: the gallery system is collapsing under its own weight during the most unstable geopolitical period since World War II.

Black Rocks Geopolitical Threat Dashboard: https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/insights/blackrock-investment-institute/interactive-charts/geopolitical-risk-dashboard

The data is unambiguous. Global conflicts have reached levels not seen since 1945, from Ukraine to Gaza to escalating tensions across the Indo-Pacific. This isn't a temporary blip—it's a fundamental restructuring of the global order, and it's putting enormous pressure on economies worldwide. When institutional investors and collectors are watching potential nuclear flashpoints and unprecedented migration crises, art becomes a luxury few can justify.

But the real crisis isn't geopolitical—it's structural.

The gallery model, with its standard 50% commission, made sense when there was a thriving middle class capable of discretionary spending on emerging artists. That middle class is gone. Wealth concentration has created a two-tier market: ultra-high-net-worth collectors buying established names at auction, and everyone else priced out entirely. The traditional gallery, which depends on a steady flow of mid-tier collectors building collections over time, is caught in no-man's-land.

Here's the math that doesn't work: An emerging artist needs to price work high enough that splitting revenue 50/50 with a gallery still covers materials, studio rent, and somehow—laughably—living expenses. But those prices immediately place the work beyond reach of the very collectors who would have historically built that artist's career. The gallery, meanwhile, needs enough sales volume to cover prime real estate in major art centers. Neither side can make the equation balance.

The "strategic pause" language suggests this is a conscious, controlled decision—savvy dealers taking a beat to reassess. The reality is simpler: the model is broken. Galleries are closing, consolidating, or pivoting to private sales and art fairs because the overhead of maintaining physical spaces no longer pencils out.

What's actually happening is a forced reckoning. Artists who spent years cultivating gallery relationships are discovering those relationships were always contingent on market conditions that no longer exist. Collectors who built holdings on the promise of appreciation are finding their "investments" were speculative at best. And galleries that positioned themselves as essential intermediaries are learning they've been disintermediated by direct artist sales, social media, and online platforms.

The geopolitical instability isn't causing this crisis—it's exposing it. The art market operated on the assumption of continuous growth, stable wealth accumulation, and predictable cultural institutions. All three assumptions are now demonstrably false.

So yes, let's pause. But let's be honest about what we're pausing from: a fundamentally unsustainable system that worked for a specific historical moment that has definitively ended. The question isn't when the market recovers—it's what replaces it

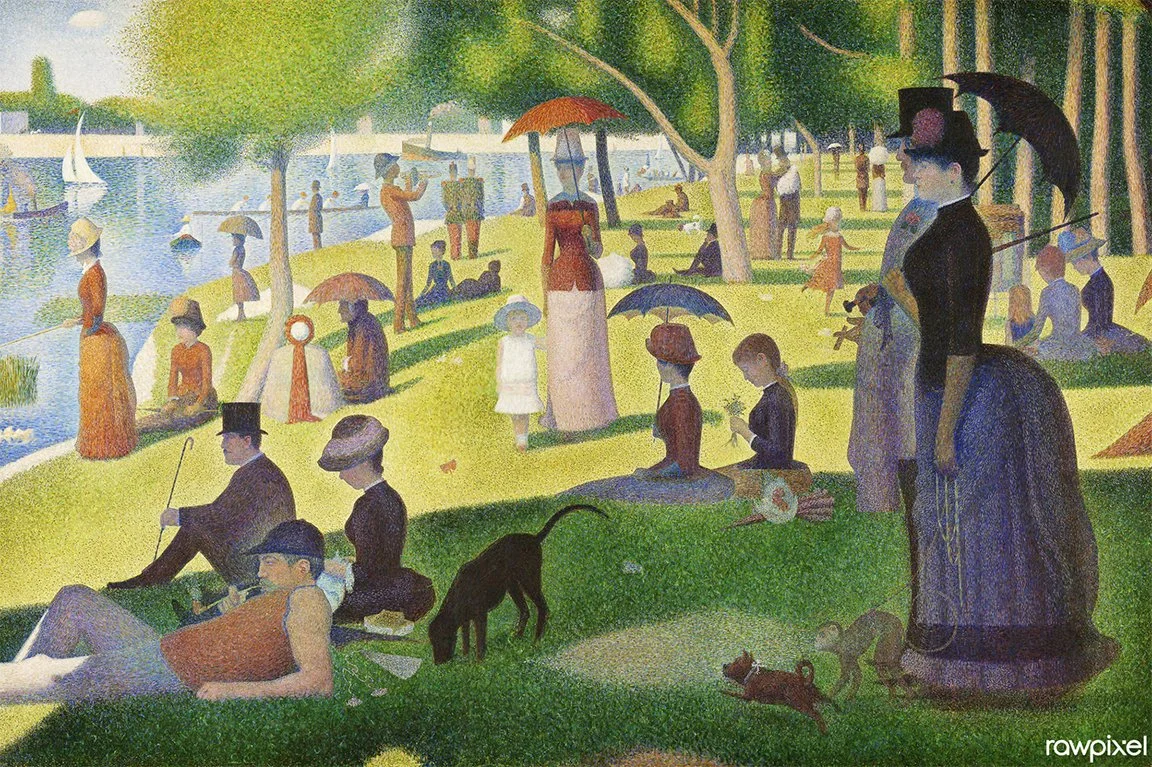

Ariana Grande and Jonathan Bailey Will Star in a Musical Based on Georges Seurat painting "A Sunday on La Grande Jatte." /

File:A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (1884) by Georges Seurat. Original from The Art Institute of Chicago. Digitally enhanced by rawpixel. (50434734621).jpg

Sunday in the Park with George depicts the fictional tale of how French post-Impressionist artist Georges Seurat came to create A Sunday on La Grande Jatte. Crafted from 1884 to 1886—along with a painted border that was added from 1888 to 1889—this work of pointillist art is the artist’s largest and most well-known creation. [Link] Wish I could go.

The painting jumpastarted Seaurat career, and two generations or so later Roy Lichtenstein’s

The World’s Most Venerated Museums — and What Each Does Best /

The World’s Most Venerated Museums — and What Each Does Best

Calling any museum the most venerated in the world is a bit like naming the single greatest book ever written. Reverence depends on culture, history, power, access, and—crucially—what you believe museums are for. Are they vaults of civilization? Moral archives? Aesthetic temples? Or living classrooms?

That said, a small group of institutions consistently rise to the top for their collections, influence, and sheer gravitational pull on global culture. Four stand apart not just for what they hold, but for what they represent.

Below is a concise tour of these giants, with a “Best in Show” for each—what they do better than any other institution on Earth.

Louvre Museum — Best in Show: The Totality of Art History

If museums had a capital city, the Louvre would be it.

Housed in a former royal palace, the Louvre is less a museum than a compressed civilization. From Mesopotamian reliefs to Renaissance masterworks, it presents art history as an unbroken human project spanning millennia. Its scale alone is staggering—but its true power lies in juxtaposition: sacred next to secular, imperial next to intimate.

Best in Show:

🏆 The most comprehensive, end-to-end narrative of human artistic achievement ever assembled.

This is not a museum you “finish.” It’s one you orbit for a lifetime.

British Museum — Best in Show: Civilization as Artifact

The British Museum is controversial—and inseparable from that controversy. Born of empire, its collection reflects the reach (and violence) of global extraction. Yet it also offers something unique: civilization seen through objects, not paintings or saints, but tools, tablets, fragments, and inscriptions.

Standing before the Rosetta Stone or Assyrian reliefs, you are not admiring beauty so much as decoding humanity.

Best in Show:

🏆 The greatest archive of human material culture ever assembled.

It asks uncomfortable questions—and that may be its most important function.

Vatican Museums — Best in Show: Art as Divine Instrument

No institution demonstrates the marriage of power, belief, and beauty more clearly than the Vatican Museums. This is art not merely collected, but commissioned as theology. Every corridor reinforces the idea that beauty can persuade, instruct, and sanctify.

The Sistine Chapel alone justifies the Vatican’s place in history—but the surrounding collections reveal centuries of deliberate aesthetic strategy.

Best in Show:

🏆 The most concentrated example of art used as spiritual and political force.

Even for non-believers, the experience is undeniable—and overwhelming.

Metropolitan Museum of Art — Best in Show: Cultural Democracy

The Met is often described as America’s Louvre, but that sells it short. What makes the Met exceptional is not just its holdings, but its openness. Ancient Egypt, medieval Europe, Asian dynasties, African sculpture, American modernism—everything coexists without hierarchy.

It is encyclopedic without being imperial, grand without being remote.

Best in Show:

🏆 The most accessible and pluralistic world-class museum on Earth.

The Met doesn’t tell you what culture is—it invites you to explore it yourself.

Final Thought: Reverence Isn’t About Size

Each of these museums is venerated for a different reason:

The Louvre preserves continuity

The British Museum preserves evidence

The Vatican Museums preserve belief

The Met preserves participation

Together, they reveal a deeper truth: museums are not neutral. They are mirrors of how societies understand themselves—and what they choose to remember, justify, or celebrate.

And perhaps that’s the real “best in show”:

not the objects on the walls, but the stories we still argue over when standing before them

Elite gallery closings: like rats leaving a sinking sink /

Why the Art Market Isn’t in Recession — It’s Collapsing, and That’s a Good Thing

These days, pundits talk about an “art market recession.” But if you look beneath the surface — past the auction hammer prices and glossy fair booths — what’s really happening is more structural: the old art market is breaking down, not just slowing. Iconic galleries that once defined contemporary art’s commercial sphere are collapsing or being forced to reinvent themselves. Meanwhile, technological change, shifting capital flows, and deep economic uncertainty are unraveling the old order.

In an unstable global economy — with geopolitical tensions, shaky markets, and oligarchic capital flight — billionaires like Warren Buffett, Jeff Bezos, and Elon Musk are signaling caution. Their moves off Wall Street and into diversified holdings should be taken seriously: capital is seeking safety and new vectors, and the traditional art trade isn’t immune.

So where does this put someone like me — a practicing artist who refuses to be hemmed in by extractive gatekeepers and backroom profiteers? It’s simple: I’m becoming my own gallerist. And this moment — precisely because the old market is fragmenting — is the right time for it.

The Signals Are Clear: Galleries Are Closing Their Doors

This isn’t rumor or hearsay. In the past year alone:

Kasmin Gallery, a New York institution representing major contemporary voices and estates, announced it will close after 35 years — with its leadership transitioning into a new venture of their own.

Clearing Gallery, active in NYC and LA since 2011 and known for championing mid-career artists, publicly stated that there was “no viable path forward” under the existing gallery model.

High Art, the influential Paris gallery that helped launch artists into global prominence, recently shuttered its physical space after 12 years.

Smaller and mid-sized spaces — from Blum in LA to Venus Over Manhattan and others — have either closed, downsized, or exited prime markets entirely.

Even longstanding galleries like Tanya Bonakdar’s LA outpost and Paris–NY galleries such as Galerie 1900–2000 have retrenched in the face of declining foot traffic and sales.

This wave of closures isn’t isolated or anecdotal — it’s systematic and widespread.

What This Really Means: A Collapse of the Old Order

We hear talk of “a slowing market” or “retraction” in press releases, but the scene on the ground tells a different story: the traditional art-dealer infrastructure that once ferried artists into commercial and institutional prominence is disintegrating. The reasons vary — rising operating costs, fewer deep-pocketed buyers, inflationary pressures — but the effect is the same: the gallery as the central broker of artistic value is dying.

This is not a recession in the Keynesian sense — a temporary dip before recovery — but a death spiral of an unsustainable, extractive ecosystem where:

Galleries with huge overhead and narrow profit margins can no longer survive.

Young collectors are wary of spending six- and seven-figure sums in opaque markets.

Auctions and fairs increasingly dominate as speculative venues, not sustainable support structures for artists.

In short, the art market’s traditional economic model — reliant on exclusivity, speculation, and middle-men margins — has been outpaced by broader cultural and financial shifts.

The Bigger Context: Unstable Capital and Uncertain Times

We can’t divorce this art-world collapse from the global economic picture. Capital is flowing away from risky equities into alternatives: tech, real estate, crypto, and private ventures. In times when billionaires adjust their portfolios toward resilience rather than risk, luxury markets like contemporary art are among the first to feel the chill.

This is not just about taste or market fashion — it’s about capital sentiment. When the wealthiest investors hedge and retreat, speculative markets tied to discretionary spending shrink faster than you think.

So Where Does That Leave Artists, Collectors, and the Public?

Liberated.

While the old system contracts, new structures are emerging:

Artists no longer need gatekeepers to access audiences.

Collectors can transact directly with artists, or through decentralized networks.

Technology — from augmented reality exhibitions to blockchain-based provenance systems — removes artificial scarcity and middlemen arbitrage.

What once required a storied gallery on a blue-chip roster now only needs community, transparency, and creativity.

I’m not predicting the death of art — only the death of a specific commodification mechanism that enriched profiteers while isolating artists and audiences. As galleries fall, the art world’s cultural center of gravity shifts toward practitioners and patrons themselves.

I’m stepping into that space, not just as an artist but as my own gallerist — aligning my practice with the real values of art, not with inflated market machinery. This is not a collapse; it’s a reconfiguration — one long overdue.

This is the best part of being an artist.. /

…Is showing your work and seeing how people react. The year 2025 was very good to me creatively and more. I sold 8 pieces, and gave away three or four. A few of my pieces are now living in Asia, and one is in London; all of them are moderately big pieces, too. In a couple of days, it's the new year, and back to work I go. I have studying JW.M. “fog-scapes,” and I might do some sunrises as he did, but in my own way, that is. I want everyone to have an affluent year and make many friendships. I love you all!

YES! — The Art Market Is Changing — Artists and Collectors Are Growing Closer, and That’s How It Should Be /

The latest Art Basel and UBS Global Art Market Report shows that the art world is at a turning point — not simply because sales figures dipped, but because the structure and dynamics of collecting are evolving in ways that benefit artists and the larger cultural ecosystem. The narrative of a “market crash” is an easy headline, but the deeper shifts are far more interesting and far more promising than most analysts are letting on. Art Basel+1

In 2024 the total global value of art sales declined roughly 12%, down to about $57.5 billion. On the surface that sounds dire, but look closer and the pattern tells a much richer story. Sales by value dropped largely because the high-end segment — especially works above $10 million — saw a sharp contraction, while overall transaction volume actually grew by about 3%. There were more sales, not fewer, just at different price levels than before. Art Basel+1

This is important. A market dominated by mega-sales at auction doesn’t tell us about the health of the creative ecosystem. Those trophy sales mostly reflect a very small group of ultra-wealthy players and are highly sensitive to economic conditions. The fact that total transactions increased — and that the lower-priced segments continued to gain momentum — shows that a broader base of collectors is participating. Those are the kinds of buyers who don’t just buy a painting as a financial asset; they buy because they feel the work, they engage with it, and they live with it. Artsy

What’s more, the surge in smaller dealers’ sales and the stability of online channels means that art is being discovered and transacted in more decentralized ways than ever before. Smaller dealers (with annual turnover under $250,000) experienced some of the strongest sales growth as a segment, and online sales — although slightly down from their peak — remain far above pre-pandemic levels and have become a key entry point for new buyers. Artsy

To artists, this shift should feel familiar. It mirrors how art emerges in a culture — not from isolated elite tastemakers, but from many individual relationships between creation and perception. If collectors become more numerous, more diverse in taste, and less dependent on million-dollar benchmarks, then the mechanism of value becomes more directly tied to the work itself, not just to its trophy status. In other words, it brings the market closer to the artists and their audiences, rather than further away behind institutional opacity.

Where some reports emphasize how Gen Z and younger collectors are still a minority with substantial means, the more useful interpretation may be that these newer collectors are reshaping the pathways by which art is discovered and valued, even if they aren’t yet the dominant spending cohort. They are not just buying what the galleries tell them to buy; they are discovering art through digital platforms, communities, and word-of-mouth. In this sense, the way art travels is becoming more horizontal rather than vertical — closer to direct engagement between creator and viewer. Artsy+1

Another notable trend is the rising role of women collectors. Several analyses of the UBS/Art Basel research find that women are not only spending more on art than men on average but are also more likely to buy works by artists they don’t already know. This is not insignificant. Gender diversity in the buyer base can help diversify the kinds of art that get supported — bringing new voices, new styles, and new ideas into the marketplace. United States of America

Taken together, these shifts — more transactions at accessible price points, stronger engagement with smaller dealers, digital discovery channels, and more diverse buyers — suggest that the art market may be democratizing its mechanics even as it contracts at the very top. That’s no small thing. It means the power to shape taste and cultural capital is beginning to shift away from a handful of elite gatekeepers toward a broader network of collectors and creators. That’s good for artists. It’s good for culture. And it’s precisely how a living, breathing ecosystem grows. Artsy

Of course, caution is still warranted. A market with fewer high-end sales can feel discouraging to big galleries and auction houses that depend on blockbuster results. But if the market recalibrates toward meaningful engagement rather than spectacle, then the conditions for artistic flourishing improve. Artists are not measured solely by million-dollar price tags; they are measured by how often their work connects, changes minds, and enters lived experience. And if more collectors — young or old, cautious or confident — are participating with that mindset, then the future of art is not shrinking. It is realigning. Art Basel

The UBS/Art Basel data may look like a bearish market at first glance, but the real takeaway is that sales value is only one dimension of health. The qualitative shifts — more diverse buyers, growth at grassroots price points, and a digital infrastructure that bypasses traditional gatekeeping — point to a more interconnected future between artists and collectors. In that sense, the art market is not collapsing; it’s maturing.

SUPER CRITICAL LIQUID — WHERE WATER BECOMES ORIGIN /

Before Super Critical Liquid became a series of paintings, it began with a simple thought:

Water is the quiet architect of everything alive.

We forget this, because water is everywhere — in our bodies, our memories, our oceans, our storms — but nothing on Earth exists without it. Carbon and water are the co-conspirators of life. One provides the structure, the other provides the medium. When they meet, things happen: cells form, chemistry wakes up, life begins to sketch itself into being.

That’s why I wanted to understand water when it reaches its most intense state — the moment where it stops behaving like “just water” and becomes something transformative. Scientists call that moment super critical liquid. I think of it differently:

It’s the threshold where matter becomes possibility.

Water: The First Home of Life

Every ocean wave is older than civilization.

Every drop of rain is recycled from ancient seas.

Every living thing on Earth traces its lineage back to water.

Life didn’t begin in soil or air — it began in the deep.

Water held us, protected us, and gave us room to experiment. Even now, humans are still made of it. Nearly two-thirds of the body is water, and most of our internal chemistry occurs in miniature oceans inside our cells.

We may walk on land, but biologically, we never left the shoreline.

Water Is More Valuable Than Gold

Human history proves this again and again:

We have fought over rivers.

We have guarded wells.

We still negotiate over water rights with more intensity than any mineral or metal.

Gold is luxury.

Water is survival.

Civilizations rise where water flows.

Civilizations fall when it disappears.

We can argue about politics, borders, ideologies — but water remains the ultimate truth-teller. It always wins.

Water as My Safe Harbor

People often ask why water appears so frequently in my work.

It’s simple: water is where I feel most myself.

When I swim, my mind clears.

When I stare at the ocean, I feel perspective return.

Water absorbs anxiety, distractions, deadlines, and noise.

It is the one element that holds me the way it once held the earliest forms of life — without condition or expectation.

So when I paint Super Critical Liquid, I’m painting more than a scientific idea. I’m painting the feeling of water when it becomes absolute:

the moment where it stops being background and becomes a force.

For me, water isn’t just symbolic.

It’s home.

It’s history.

It’s refuge.

It’s the element that resets me so I can create again.

Why I Paint This Series

Super Critical Liquid isn’t meant to be literal.

It’s meant to capture the emotional state where pressure, heat, and experience combine — and something new is born.

It’s about transformation.

It’s about the place where boundaries dissolve.

It’s about water becoming more than itself, the same way we sometimes become more than our circumstances.

Water made life.

Water makes us.

And in my studio, water makes art.

ECTROPY & THE PAINTER’S HORIZON LINE /

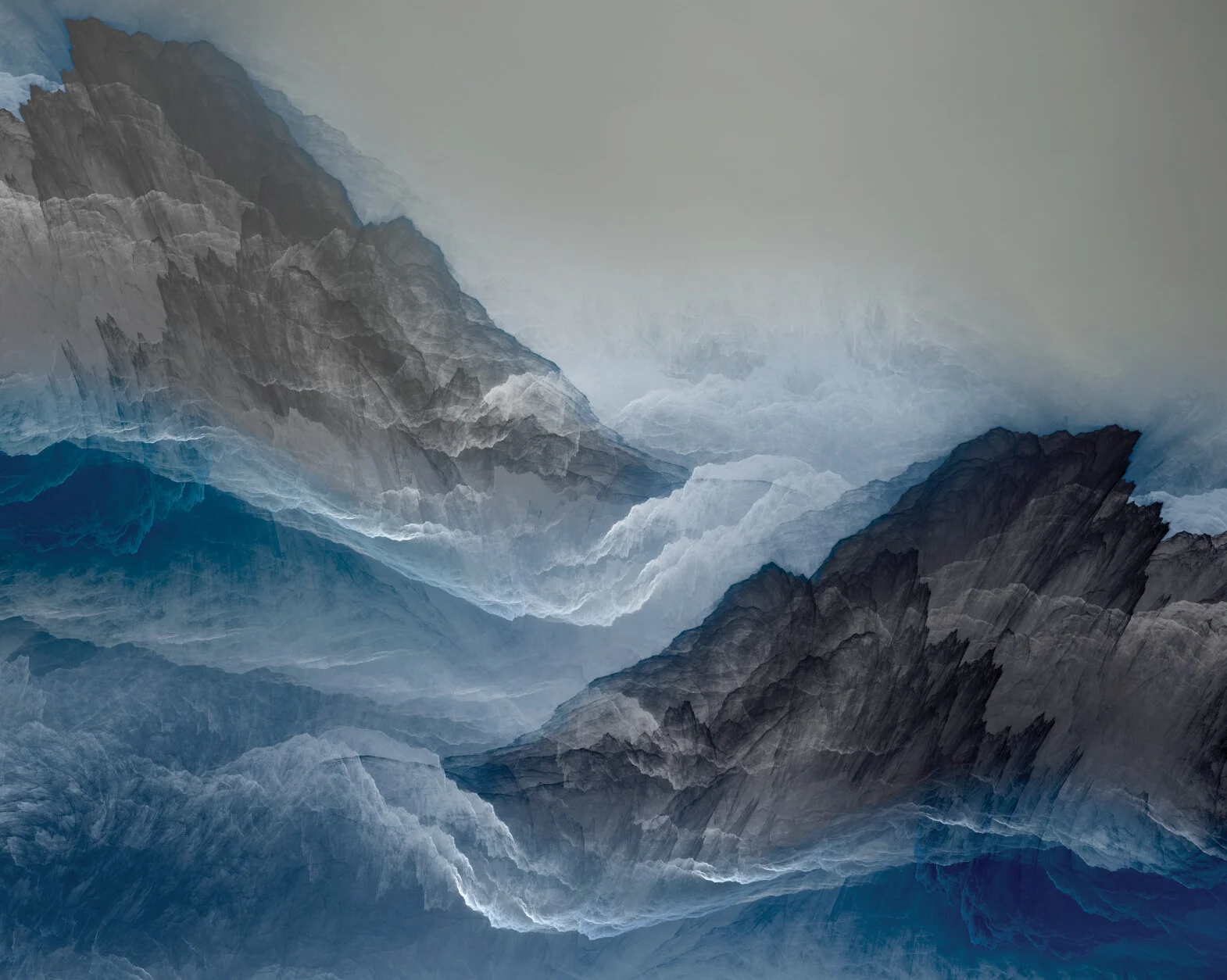

A fractal Flame collage from my Ectropy series. 40”x 60” inches. Edition of 8

Ectropy is the opposite pressure of entropy — the rising force of complexity, structure, memory, and life. Where entropy unravels pattern into noise, ectropy gathers it. It is the improbable tendency of the universe to build stars, cells, minds, civilizations — anything that grows instead of collapsing. In this sense, a painting is not merely an artwork. It is an ectropic act.

To paint is to resist dissipation. Pigment is chaos until guided; canvas is void until shaped. Every stroke interrupts disorder, turning raw material into meaning. A horizontal work intensifies this feeling — read like landscape, strata, horizon-line — a geometry of geological time. Such a format implies aeons, sediment, and a universe thinking in layers rather than moments.

In this piece the concept deepens into the Jacob’s Demon idea: imagine entropy has already consumed nearly all that could be destroyed. Stars dimmed, heat spent, chaos fully expressed. And then — in the stillness after collapse — a new order begins. Not born from violence, but from the exhaustion of it. When there is nothing left to break, ectropy becomes inevitable. Gentle. Patient. Sublime.

Fibrous currents gather like the first architecture of matter. Light folds inward as if remembering how to ignite. It is not the beginning of the universe, but the second beginning — the moment when creation returns after ruin. A quiet genesis.

To collect such a work is to hold a fragment of that renewal — a vision of order rediscovering itself. The painting asks one question, softly but permanently: What forms rise when the universe is finally quiet enough to grow again?

What startles me most, and what convinces me we are knowledge-throttled creatures, is the nature of infinity itself. Not as something large, but as something for which the mind has no place to stand. Infinity has no first cause, no origin point, no final hour. It isn’t just beyond measurement — it exists outside the very grammar of thought. We can say the word, but we cannot hold the concept. Try to imagine a beginning with no beginning, or a boundary that never arrives, and the mind buckles like a bridge with one beam missing. It makes me wonder if some ideas lie permanently outside human comprehension — not because they are hidden, but because our brains were not built to contain them. And in that realization, I feel two things at once: awe, and a small, claustrophobic shiver. As if infinity isn’t a horizon — but a window we can see through, yet never climb beyond.

Since "Wicked" and "Wicked Forever" is a thing, I created this “bank note” for the "Wizard of Oz" — 100 Emeralds cash note /

The serial number birth date and passing date. Some say the Wizard of Oz was an allegory.

L. Frank Baum, a journalist at the time in Chicago, is supposed to have composed the Wizard of Oz as an allegory depicting these events. Thus, according to this interpretation, Dorothy (representing America and her honest values) wearing silver shoes (representing the free silver coinage) recruits the Scarecrow (representing the American farmer), the Tin Man (representing the American worker), and the Cowardly Lion (William Jennings Bryan), to accompany her on the yellow brick road (representing the gold standard) to the Emerald City (Washington, D.C.) to plead with the Great Wizard (the Democratic president Grover Cleveland) of Oz (an ounce of gold) for free silver coinage. In the process, Dorothy and her companions also battle the Wicked Witch of the West (William McKinley, the Republican presidential nominee in 1896). Unlike the Democrats, McKinley was against abandoning the gold standard in favor of a more expansionary bimetallist (gold and silver) system. As it turned out, however, the issue of the silver coinage became moot with the new gold discoveries in Alaska in the 1890s, which served to undermine the Democratic platform and, thus, to cost the Democrats the US presidency both in 1896 and 1900. ref: LINK

I love the are of money and I don’t mean Finance, I like the engraving, the reliefs on the coins, and even the typography. One day I decided to make my own version. Hope you like it.

What is the 70/30 rule for artists — it's not pricing! /

The 70/30 rule in art is a compositional and process guideline that can be interpreted in two main ways: as a time allocation for creative workflow or as a balance of visual elements within a piece. The time-based interpretation suggests spending 70% of the time on planning, sketching, and problem-solving, and 30% on execution and detailing. The visual interpretation advises a balance where 70% of the artwork is the dominant, less detailed area, and 30% is the dominant focal point with more detail and visual interest.

I endorse this percentage for those who are detail-oriented and have a passion to articulate their vision to the ne plus ultra! But I am not that guy. I will do everything out of order or all at the same time. I Sketch, Sketch, Sketch, then I break, break, break, and I spend 80% of my time fixing what I broke. “After climbing up that mountain,” it is then that I realize the original broken version 1.0 was the best version of all. So I revert to that version and, with renewed interest, I spend days working on the final version, coloring it, and then completing it.

Finishing a painting is quite an elevated feeling. Lucien Freud said something along the lines of that he knows when a painting is completed if it looks like somebody else did it. As for me, that feeling is mutual. After admiring the work for about 2 weeks or so, I want to go back to it and add to the environment as if I were an explorer. Then I call it a series, and I start another version. Here are two “aliterations” of the Precipice Series below. I was so excited with the first, I wanted to experience more of the “space.” A third is coming — more fog, maybe snow — because I want to keep stepping into that space and see what awaits past the next ridge. Call it serendipity or stubborn imagination — I paint because I’m curious what comes next.

Precipice series: Precipice & Fog 40” x 30”

Precipice Series: Precipice & Ice 40” x 60”

Artist’s Resale Rights Look Great on Paper — but Far Less Great for Artists, Collectors, Gallerists, and Industry Money Laundering /

Canada’s proposed Artist Resale Rights bill is a Trojan Horse…” to avoid the extra adjective (the) and tighten the opening rhythm.

Canada’s 2025 federal budget introduced an Artist’s Resale Right, a policy intended to grant creators a five percent royalty fee on every future sale of their work. The proposal has been marketed as long-overdue fairness, a corrective meant to help artists participate in the rising value of their own creations. On paper, the idea feels noble. In practice, the effects are far more complicated than the headline suggests.

ARR transforms a resale into something larger than a simple exchange between two parties. A resale becomes a recorded financial event that triggers a royalty obligation. That royalty is then treated as taxable income for the artist. At the same time, the resale itself becomes a taxable, traceable moment in the artwork’s lifespan. The artist receives a payment, the government records a transaction, and the asset becomes more visible within the financial system. What appears to be a small administrative detail is actually a structural shift in how art circulates.

The core of ARR lies in the mechanism that governs every resale. When a work is sold on the secondary market, the buyer pays the agreed price. A percentage of that price is diverted as a royalty owed to the artist or the estate. The artist must declare that royalty as income, and the resale is documented as a taxable event for the government. No transfer can occur quietly. Each sale creates a financial footprint that cannot be erased. As a result, the government benefits twice. It collects new taxable revenue, and it gains a clearer view of where high-value art resides, how it moves, and how much it is worth.

This structure also reshapes behavior. Under the old system, some collectors and intermediaries engaged in strategic resales to inflate an artwork’s value. A painting could move between shell companies or trusted associates, generating a series of “record” prices that created the illusion of rising demand. ARR makes such practices expensive. Each artificial resale requires a royalty payment and triggers a taxable event. The economic friction discourages the inflation loop. Price manipulation becomes a costly habit rather than a profitable strategy.

Supporters of ARR emphasize fairness. They argue that artists deserve a share of the long-term value generated by their work. Historically, a painting could sell for a modest sum early in an artist’s career and then appreciate dramatically later on, enriching dealers, collectors, and estates while the creator received nothing. ARR attempts to correct this imbalance. For certain artists, especially those whose work circulates actively in the secondary market, the additional income could provide meaningful support.

The concerns arise when the financial implications are examined more closely. A royalty functions as a fee added to every future sale. The artist receives the payment but must pay taxes on it. A single resale becomes a dual tax event. Buyers may hesitate to acquire works that carry perpetual obligations. Some may shift toward assets without recurring royalties. And as lifetime costs become part of the purchasing calculation, initial prices may rise to absorb future expenses. Ironically, a system designed to help artists can end up pushing their primary market prices higher, making their work less accessible to new collectors.

There is also the issue of transparency. Governments dislike opaque markets because opacity hides financial activity. ARR makes valuable artworks visible in ways they were not before. Every resale is documented. Every price becomes part of a traceable chain. Every movement of the artwork leaves a digital shadow. For honest collectors, this visibility is benign. For those who use art to store wealth discreetly, obscure transactions, or move funds covertly, this evolution is inconvenient. The painting becomes a kind of Trojan Horse. It enters a private home, a vault, or a freeport carrying not only ideas and emotion but a permanent record of ownership, value, and movement.

Yet ARR is not without potential benefits. It can stabilize artist incomes, deter fraudulent pricing schemes, and limit opportunities for laundering. It brings a measure of honesty to a market that often thrives on ambiguity. But the price of this honesty is structural change. Paintings behave less like free-floating cultural objects and more like semi-regulated assets with embedded obligations. Collectors may adapt. Gallerists may struggle. Artists may gain a small but steady income stream, yet also find their primary market shifting around them in unpredictable ways.

The larger question is not whether ARR is fair, but what it transforms. It promises to reward artists, yet it also pulls art deeper into the architecture of fiscal transparency. It speaks the language of equity, yet creates new layers of cost. It aims to correct a cultural imbalance, yet inadvertently alters how art is bought, sold, held, and perceived.

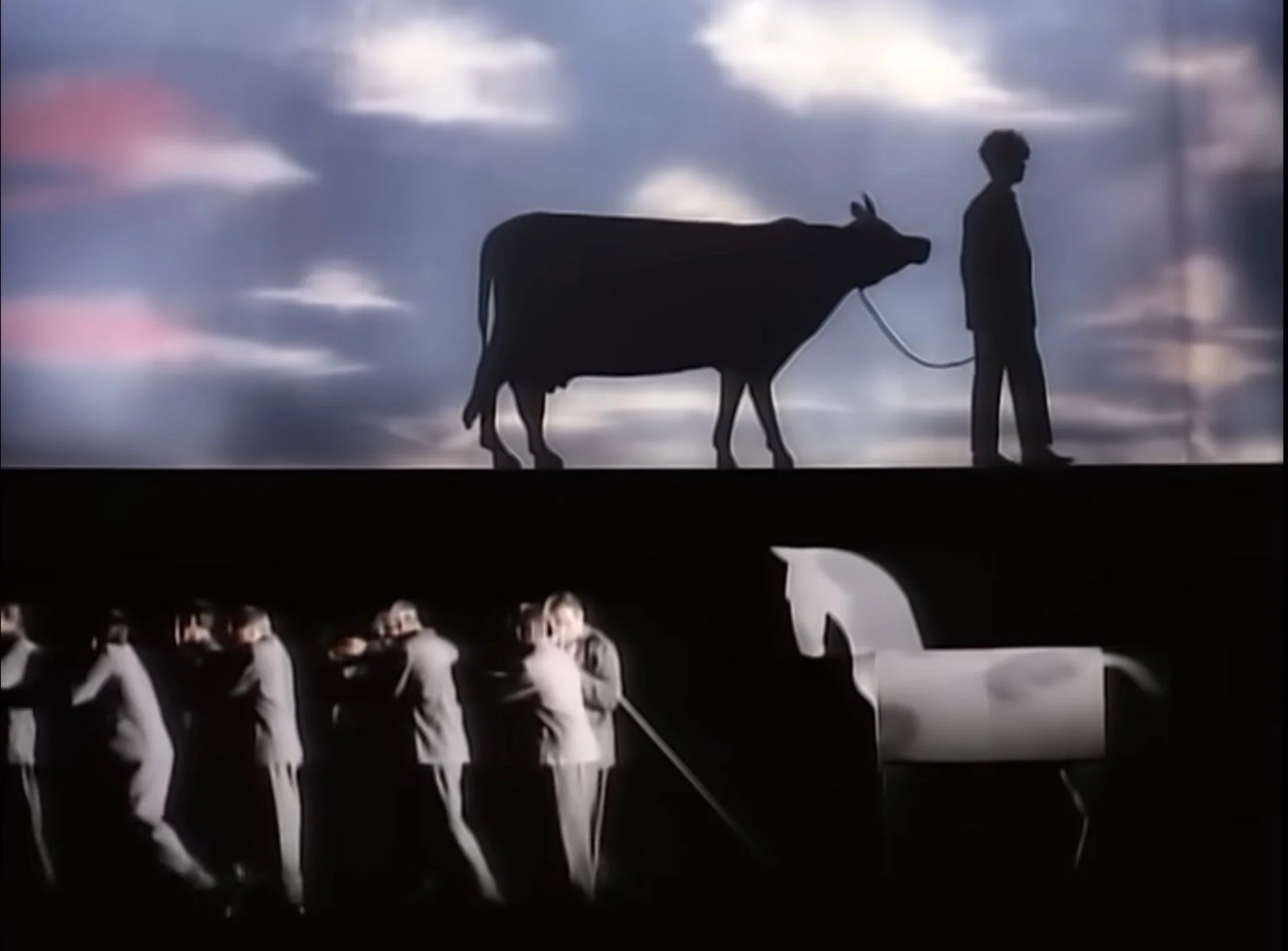

Echo & the Bunnymen's "Bring On The Dancing Horses" is the perfect vehicle for the Art as Trojan Horse metaphor. The song's compelling rhythm and aesthetic allure act as the vessel, bypassing conscious defenses to deliver its cargo: deep ideas, surging passions, and the inspiration that compels action. Now this Trojan Horse could be used for an extra 5% for taxation,

Art has always carried ideas into private spaces like a Trojan Horse. It slips past defenses and changes minds, one viewer at a time. ARR inserts a second Trojan Horse inside the first. It carries financial disclosure, tax events, and asset visibility into the same spaces where ambiguity once thrived. Some will welcome this. Others will resist it. Everyone in the art ecosystem will be forced to adapt.

ARR may help artists in certain circumstances. It may harm them in others. It may strengthen the market, or it may compress it. What is certain is that ARR changes the very identity of art within a modern economy. A painting becomes both an act of human expression and a permanent ledger entry that follows its owners wherever it goes.

This is a new era for art. The question is whether this era strengthens culture or slowly transforms it into an industry where every canvas carries not only a vision, but a paper trail.

WIll artists, art consultants, and advisors, fill the gallery void if the industry collapses /

L.A. Art Show 2023 — exhibiting my work with bG Gallery.

In my opinion, galleries are collapsing under the weight of their own inefficiencies and conflicts of interest. The economics alone are absurd. Galleries routinely take a 50% cut of every sale; a markup no other industry would survive, thereby leaving artists with a fraction of the value they create. And buyers, ironically, become the victims of this inefficiency: they pay premium prices inflated not by artistic merit, but by an outdated distribution system.

Now, if that weren’t enough, a tiny, arcane circle of galleries decides who the “cool kids” are. A handful of power brokers anoints the chosen few, shapes museum programming, and manufactures cultural legitimacy. Everyone else, artists, collectors, and even institutions, is downstream of their decisions. But if anyone deserves to be closest to the source, it’s the people actually buying the art.”

The efficiencies extend far beyond simple communication. Commissions are dramatically better in this emerging model, with artists retaining far more of the value they create. Museum curators are freer as well — able to champion the work they believe in without worrying about alienating a museum director who answers to a mega-gallery donor. And consultants handle the tasks galleries once monopolized: they help collectors build thoughtful, balanced portfolios for clear, transparent, nominal fees. No hidden markup. No political pressure. No gatekeeping.

If I were responsible for moving human culture forward — if it were my job to decide which works deserve to enter the fine art canon — these are the criteria I would use: Originality, Contribution, and Continuity (OCC) as my benchmark... I picked a handful of well-renowned artists below to illustrate how Originality, Contribution, and Continuity can be a valid way to judge museum-grade work.

Claude Monet:

Originality: Monet did not paint water lilies; he painted the physics of perception. His originality was not in inventing Impressionism outright, but in pushing it past experiment and into clarity — revealing how light, color, and atmosphere become experience inside the eye. He dismantled academic realism and replaced it with a new visual truth: the moment as felt rather than the scene as recorded.

Contribution: Monet was not the first Impressionist, but he is the one who solidified Impressionism into a movement. With Impression, Sunrise, he transformed scattered innovations among artists into a coherent genre, a visual philosophy with momentum. He contributed more than technique; he contributed infrastructure — a shared aesthetic, a unified cause, and a cultural direction. Monet didn’t just paint the movement; he organized the gravitational center that made it unavoidable.

Continuity: Monet evolved relentlessly. From Argenteuil to the Rouen Cathedrals to the vast late Water Lilies, the thread is unmistakable: a single mind deepening a lifelong inquiry. This is continuity — not repetition but refinement, a disciplined devotion to understanding how humans perceive time and light. Monet stands as a blueprint for how an artist builds civilization: through patient, focused, enduring insight.

Georgia O’Keeffe

Originality: O’Keeffe did not paint flowers; she painted the architecture of attention. Her originality came from isolating form, stripping away the decorative, and revealing the monumental inside the intimate. Nobody before her had taken nature’s fragments — bones, blossoms, desert horizons — and transformed them into pure emotional geometry. She saw scale not as a measure of size, but as a measure of importance.

Contribution: O’Keeffe redefined American modernism by giving it a new visual grammar: clarity, distillation, and radical focus. While others looked to Europe for direction, she carved out a distinctly American visual identity rooted in light, space, and internal experience. She didn’t just contribute works; she contributed a new way of seeing — one where magnification becomes revelation and abstraction grows out of reality rather than escape from it.

Continuity: O’Keeffe’s evolution was unwavering. From the charcoal abstractions to the New York skylines to the New Mexico desert, the throughline is unmistakable: a lifelong search for the essential. She stayed disciplined, independent, and fiercely consistent in her pursuit of clarity. Her continuity was not stylistic stagnation but an unbroken deepening of vision — a sustained commitment that allowed her to shape an entire chapter of American art.

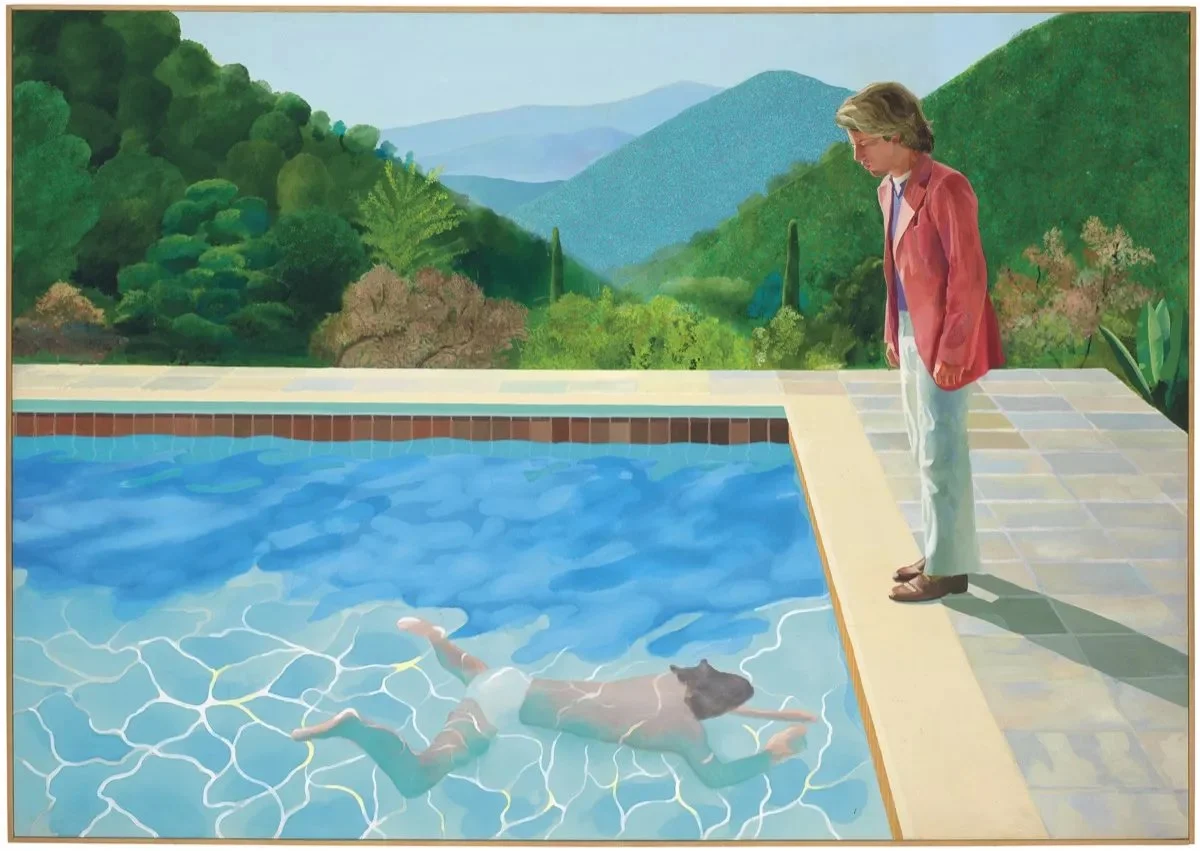

David Hockney:

Originality: Hockney’s originality lies in his persistent reinvention of vision. He questioned how we see — through perspective, memory, movement, and even screens. Whether in pools, portraits, photo collages, or iPad drawings, he explored the mechanics of looking with a curiosity bordering on scientific.

Contribution: Hockney embraced technology before it was fashionable. Photography, Xerox machines, Polaroids, faxed drawings, digital tablets — he treated each tool as a new brush, expanding the possibilities of contemporary painting. His contribution was to dissolve the boundary between medium and message, proving that innovation in tools can lead to innovation in perception.

Continuity: Though his styles shift, Hockney’s continuity is intellectual: a lifelong reinvention of how art captures experience. Every phase — swimming pools, Yorkshire landscapes, digital work — circles the same pursuit: How do we see the world, and how can art make that seeing more alive? His consistency is his refusal to stand still.

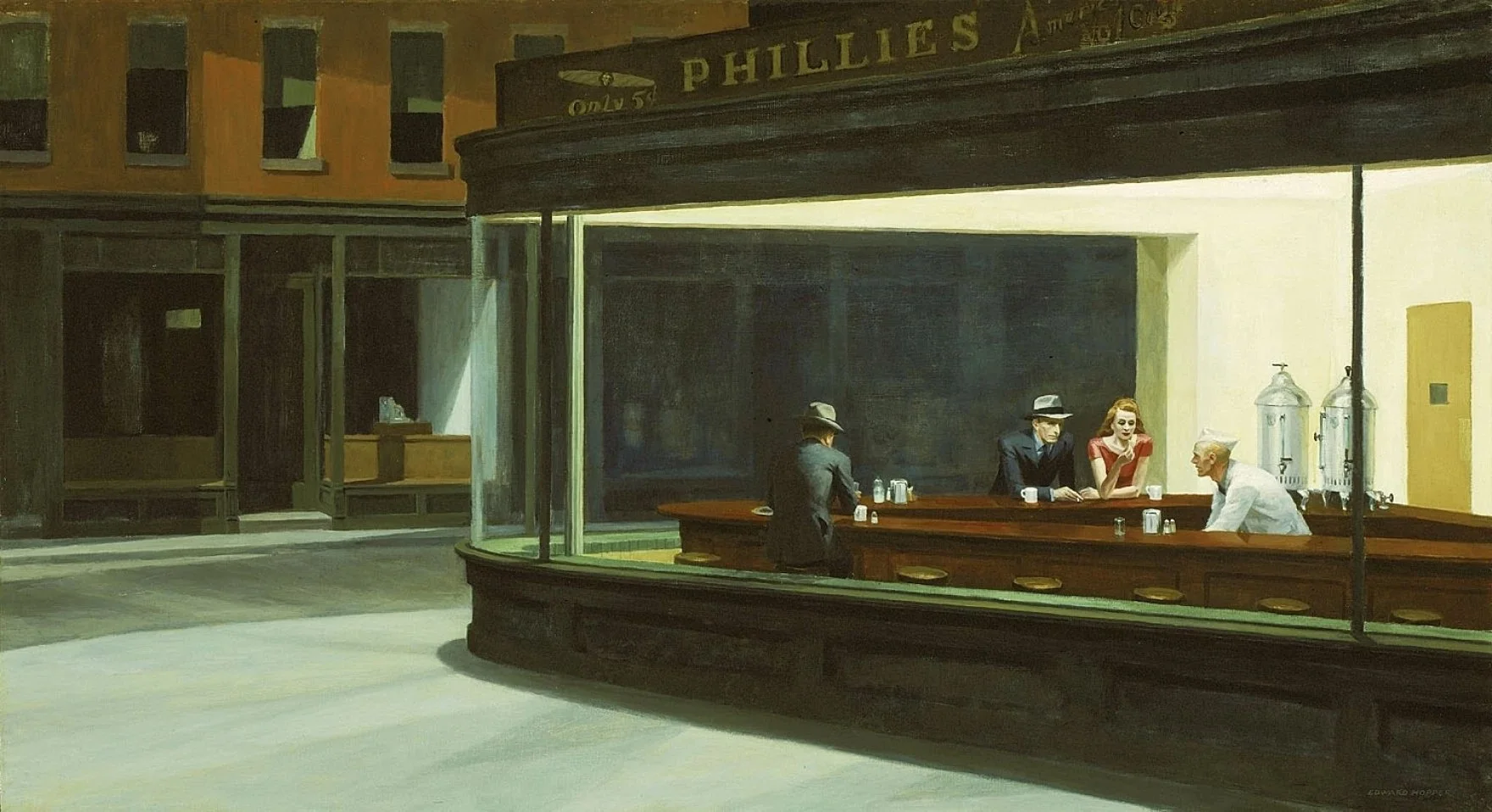

Edward Hopper

Originality: Hopper’s originality was his ability to turn isolation into a universal language. He distilled scenes into psychological states — a gas station at dusk, a woman by a window, a diner glowing in the dark — each one a quiet compression of longing and distance. He recognized that modern life was full even when nothing happened.

Contribution: Hopper contributed an atmospheric vocabulary that fused space with emotion. He redefined realism not as documentation but as mood. Through light, architecture, and silence, he created a cinematic grammar that influenced generations of filmmakers, photographers, and painters. Hopper showed that atmosphere can reveal humanity more deeply than narrative ever could.

Continuity: Hopper maintained a disciplined, lifelong exploration of solitude. From the early etchings to the final watercolors, the central inquiry never changed: How does space shape the human condition? His continuity is not monotony but mastery — a deepening of a single, resonant human truth.

Egon Schiele

Originality: Schiele’s originality lay in his line — raw, angular, electric. He stripped the body of idealization and revealed the nervous system beneath the skin. No artist before him exposed human vulnerability with such immediacy. His line was not just a tool; it was a psychological probe.

Contribution: Schiele contributed a radical new understanding of the psyche. His portraits were not likenesses but self-dissections — an unfiltered confrontation with desire, shame, alienation, and interior conflict. He forced viewers to witness the human mind laid bare, advancing the notion that art could reveal identity not as a mask but as a rupture.

Continuity: Despite his short life, Schiele’s continuity is unmistakable. Every period, early, mid, late — circles the same obsession: Who am I beneath the surface? Who are you when your defenses fall away? He deepened this inquiry relentlessly, refining it until line, psyche, and identity fused into a singular, unmistakable voice.

Andy Warhol

Originality: Warhol’s originality was not just that he painted soup cans; it was that he painted what everyone had in common. He saw the unspoken democracy of American consumption: the president drank Coca-Cola, and so did the factory worker. In a fractured society, he identified the cultural objects that unified people across class, geography, and status. His originality came from recognizing that the shared everyday object was the true icon.

Contribution: Warhol’s great contribution arrived by accident — an over-painted lip line on his Elizabeth Taylor silkscreen. That mistake transformed Taylor from a person into a construct, a symbol rather than an individual. Warhol realized in that moment that celebrities had replaced the ancient gods and goddesses: larger-than-life, endlessly reproduced, worshipped, consumed. He shifted art’s mission from depicting reality to revealing the machinery that manufactures reality — fame, commodification, myth.

Continuity: Across every phase of his career, Warhol returned to the same idea: American culture fabricates its own pantheon. From Marilyn to Mao to disaster series to Brillo Boxes, the throughline is unmistakable — a lifelong study of how icons are created, circulated, and adored. His continuity was not stylistic; it was anthropological. Warhol chronicled the birth of a new religion: the worship of the image itself.

Summation:

In the end, culture has always belonged to the people who care enough to build it — the artists who create the work and the collectors who give it a life beyond the studio. When a small circle of intermediaries controls the gate, culture shrinks. But when artists, consultants, and engaged collectors shape its direction, culture expands. It grows more diverse, more democratic, and more honest. The future of art will not be determined by a handful of galleries deciding who belongs; it will be shaped by those who recognize originality, reward contribution, and support continuity. That is how civilizations have always advanced — not through exclusivity, but through participation. The gatekeepers had their century. The next one belongs to all of us.

The Billion-Dollar Ghost /

An auctioneer’s ghost at Christie’s taking a bid from the chandelier. Caveat: I replaced the actual Christie's paintings with my own!

Every November, the auction houses stage their annual Broadway production. Christie’s rolls out its numbers, the press reacts with automatic enthusiasm, and the headlines gush about a “market rebound,” as though one evening of bidding could resurrect an entire ecosystem. This year’s script delivered the usual spectacle: $690 million in sales, $2.2 billion across the week, and a chorus of commentators insisting the art market is suddenly “healthy” again. It’s the same choreography every year, and everyone knows their role.

But none of this tells us anything meaningful about artists, galleries, or the cultural economy. It isn’t a metric; it’s a ritual — a performance meticulously engineered to maintain the aura of confidence and inevitability. And yet the punditry continues to misread the motives behind these headline-grabbing numbers. A perfect example is the $236.4 million Klimt. The press treated it as a grand gesture of cultural signaling, as if billionaires throw around a quarter-billion dollars to impress each other with taste. That interpretation misunderstands how real power behaves.

The ultra-wealthy save for “tech bros” and do not showboat. They don’t need to. They already own the infrastructure: the companies and access to media outlets to promote their wares. The people who perform status spending as if they were actors playing a part are the ones trying to climb into that world — the nouveau riche, the hedge-fund strivers, the crypto kids. They make noise because they are insecure. The mighty move quietly, through advisors, consortia, intermediaries, and shell corporations. They don’t raise paddles; they move markets.

If the rumors surrounding the Klimt are true — and they almost always are — the buyer is one of the usual suspects. Possibly a Saudi prince. Perhaps a sovereign wealth vehicle. Possibly a consortium shielding a larger political or cultural agenda. But let’s be clear: if a Saudi royal acquired the painting, it wasn’t to spark envy on Instagram. Their acquisitions are geopolitical, not social. They consolidate cultural sovereignty. They reallocate wealth outside Western banking systems. They plant seeds for future national museums. They strengthen diplomatic leverage, and this has nothing to do with bragging rights. It is statecraft dressed in silk.

Meanwhile, auction houses are hardly neutral brokers. Their business model depends on rumor, opacity, and myth-making. They thrive on choreographed suspense and whispered identities. They help launder wealth, legitimacy, and narrative in equal measure. A $236 million sale can easily be the product of a consortium — strategic, coordinated, anonymous — and the public NEVER knows. What matters is that the performance convinces the audience that the system works, that the market is strong, that the illusion is alive.

And none of this money circulates back to the people who create the work. These astronomical figures reveal nothing about rising studio rents, medical bills, debt, the instability of artistic income, or the absence of resale royalties in the United States. They do not capture how isolating it feels for an artist to watch their work become proof of a “healthy market” while the creator struggles to find the time or resources to make the next piece.

If you want to understand the fundamental economics of art, step away from the auction block and walk into any major art fair. An average painting might sell there for around $5,000. After the gallery takes its 50% percent commission, and the IRS claims its share. The artist is left with maybe $2,000 — enough to cover a month’s rent in Los Angeles if you’re lucky, or a mortgage payment in Helena, Montana. The irony is that galleries have become “the new starving artists,” operating on razor-thin margins and desperate sales. Art consultants, advisors, and even the artists themselves may end up replacing them entirely. The ecosystem is quietly cannibalizing itself while the auction houses make noise about “recovery.”

As we approach Miami Art Week, this machine will shift into full volume. Art Basel Miami Beach has become the industry’s annual sermon of optimism — the cathedral where everyone gathers to perform the fiction that everything is fine. The auction is the prologue. Basel is the crescendo. Collectors show enthusiasm for each other. Galleries take on existential financial risk to stand in the right rooms. Institutions wander the aisles to signal they still matter. Everyone pretends the system is stable because acknowledging the truth would collapse the ceremony.

The real story is not the Klimt. It’s the fiction we keep buying. A billionaire does not spend $236 million for status. That’s what the almost-rich think they do. The truly powerful shape culture, consolidate influence, and move wealth across borders in ways most people will never see. Look at J. Paul Getty, who left behind two public museums that now educate millions. Look at John D. Rockefeller, whose cultural, scientific, and social philanthropy permanently altered the American landscape. These are not gestures of vanity — they are acts of cultural engineering.

The auction room is a theater for the nouveau riche. The real motives live in the dark. And until we are willing to talk about that honestly, we’ll keep applauding the performance without ever questioning the plot.

The Art World vs. The Art Market — And Why Artists Must Always Design Our Culture /

By EU - Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2846254

Google defines the Art World as a complex network of individuals and institutions—artists, galleries, museums, collectors, and critics—interacting across overlapping spheres. It is not a monolith but an ecosystem with different values and hierarchies depending on whether you’re dealing with academia, exhibitions, or the marketplace. Under this definition, most of us working artists are firmly embedded in the Art World. We exhibit, we produce, we participate. But the true global Art Market is something else entirely.

In reality, the Art Market is small, centralized, and astonishingly selective. Eighty-two percent of sales occur in the United States, the United Kingdom, and China, and more specifically, in three cities: New York, London, and Hong Kong. Opportunity is global, but the gatekeeping is geographically microscopic.

Museum access is even tighter.

A 2015 study by The Art Newspaper found that 30% of major U.S. solo museum shows came from artists represented by only five mega-galleries: Gagosian, Pace, Marian Goodman, David Zwirner, and Hauser & Wirth. The illusion of an open field disappears once you recognize how concentrated museum pipelines are. A small number of galleries determine which artists are elevated, which careers are validated, and which works become part of cultural memory.

This creates a functional monopoly—not only over commercial opportunity, but over cultural heritage itself. When influence consolidates, cultural narratives consolidate with it. And when money becomes the primary driver, art risks becoming a commodity first and a contribution to civilization second. Paintings increasingly function like real estate or securities. If a Klimt sells for $236.4 million, it isn’t being hung over anyone’s fireplace; it’s being stored, insured, and treated as an appreciating asset held by investors.

As the market shifts toward financialization, the ecosystem around it shifts too. There are roughly 500 members in the American chapter of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA-USA). But a securities market does not require critics; it requires appraisers. It requires valuation, not interpretation. And what does that mean for artists? It means the target has changed. It means most galleries, especially mid-tier ones, struggle to compete. It means the Art Market’s priorities increasingly diverge from those of artists who are trying to create something meaningful rather than something merely tradable.

And this brings us to why artists must define their purpose clearly—because markets shift, but culture endures. Our responsibility is not to chase valuation, but to create work that speaks to human experience and to find the patrons, collectors, and supporters who allow that work to continue. Financial support is not a contradiction to artistic integrity; it is the infrastructure that makes serious work possible. Without it, there is no sustained practice, no long-term exploration, and no legacy that survives the present moment.

Which leads to the real point—the part that matters.

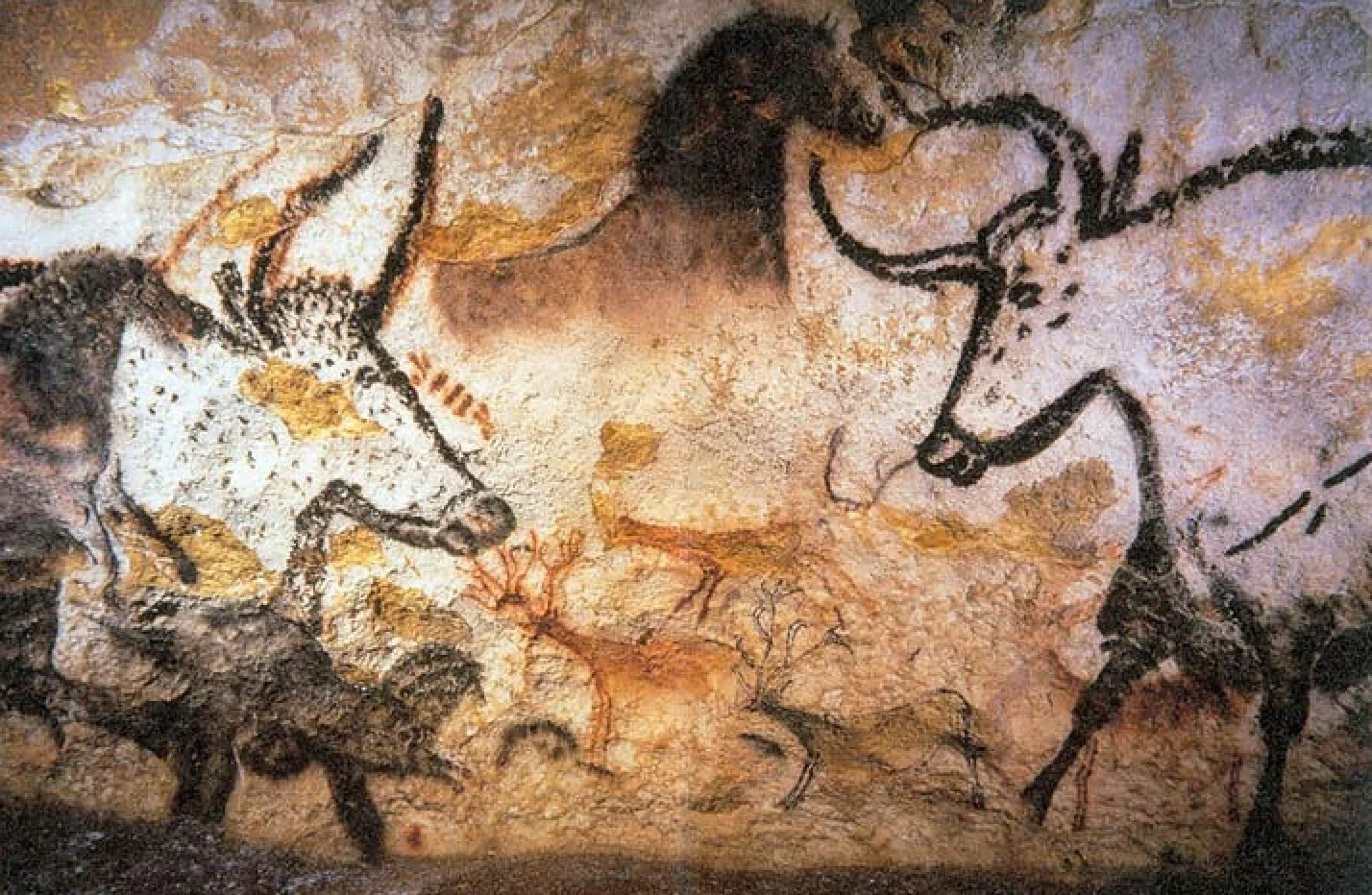

The best example of what artists contribute to civilization is still found deep underground in the caves of Lascaux. Those paintings were created without markets, without galleries, and without institutions. They were made because early humans needed to express something profound about existence. They are spellbinding not because they are old, but because they are true. Thousands of years later, they continue to mesmerize and remind us what humanity is capable of creating when the intention is pure and the vision is unfiltered.

We, too, will have to find our own “caves”—which in our era means patronage, collectors, and sustainable careers—not because art should be commercial, but because practice requires support. Once we find those caves, we must deliver work worthy of them. The duty remains the same: to create culture, to inspire civilization, and to leave behind something that proves we were here and that we understood what it meant to be human.

Who is Alma Allen, Trump’s Pick to Represent the US at the Venice Biennale. Bigger Question: Why? /

The original raison d'être (reason for being) of the Venice Biennale is to be a platform for Contemporary Art. It was intended to provide a regular, biennial platform for the discussion and exhibition of contemporary art practices, which were not typically represented in fine arts museums at the time. Let’s presume this mission statement is the true raison d'être. Alma Allen’s work is included in the permanent collections of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Palm Springs Art Museum in California.

Alma Allen's bio from ARTSY: https://www.artsy.net/artist/alma-allen

I can appreciate the craftsmanship and his choice of materials, but some of them look like chrome-plated “Tumors,” and others look like gilded detritus of smashed-up auto-body scraps. Am I jealous of this guy? — Yes, I want a foundry and factory too, but as for his vision and ideas, NO! — The New York Times described the shapes as "sensuous biomorphic forms," and 2014 Whitney Biennial co-curator Michelle Grabner selected three of Allen's large-scale sculptures for inclusion in the 2014 Biennial.

I perfectly understand why Trump chose this artist. Trump owns a gold-plated toilet and allegedly gilded molding purchased from a Home Depot catalog as decor for the Oval Office. To be fair, during a recent interview with Fox News' Laura Ingraham, Trump explicitly stated: "No, this is not Home Depot stuff," and "You can't imitate gold.” Well… you can imitate gold, and it is called gilding, but even if what they used is genuine gold leaf, it is still gilding. Trump is obviously fulfilled by facades and seemingly adores gilding, as does Allen Alma. (“Great minds think alike?” ) Maybe gilding is the message in Allen Alma’s work, and maybe gilding what is not gold is Trump’s raison d'être.

Gustav Klimt's Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer, which recently sold at Sotheby's for a record-breaking $236.4 million — Decorative art is the new ‘FINE ART’ /

In 2015, I was looking for a gallerist to hang my work. I sent out 100 postcards all across Los Angeles County, and I was lucky to receive a response from two gallerists. One of the gallerists came over to the" studio,” checked out my work, had very nice things to say about it, but he called my art” definitely not fine art but decorative art.” My polite retort: “Tell that to Gustav Klimt, Mark Rothko, and Jackson Pollock. He countered with “…Back then, their works were considered fine art.” Well, circa 2025, it looks like decorative art is the new “Fine Art.” However, what is heartbreaking is that the Klimt just sold for $237-mil million. It will now go to Freeport as an asset to be sold later on as if it were a stock or bond.

Art is not circling down a drain but some galleries are! /

The Invisible “Buyers:” How Corruption Built and Burst the Art World’s Bubble

Abstract: The high-end art market became the asset du jour after the 2008 financial crisis, not because of its cultural significance, but because its secrecy provided a perfect vehicle for money laundering and tax evasion. Through schemes involving offshore shell companies and tax-free Freeports, illicit capital created an artificial pump-and-dump bubble, driving up prices and distorting the market's legitimate structure. The inevitable legal crackdown—forcing the removal of billions in tainted funds—has triggered a long correction. This financial contraction, combined with suffocating commercial real estate costs and the erosion of the art-buying middle class, is the true, multi-faceted reason why so many honest galleries are now struggling to survive.

The Illiquidity Paradox: Circa 2014, Artwork became an“asset du jour,” which is illogical. One can sell a stock, a bond, a sliver of gold, faster than one can sell an 850-pound sculpture of a forgotten queen. But art galleries thrived in 2014 because new millionaires and billionaires were being “minted and subsequently they were hiring in their respective businesses.” Inflation was low, and jobs were numerous. It was a time to spend and share the wealth, but there was one more detail to work out… taxes!

Who wants to pay a sales tax or value-added tax of several hundred thousand dollars for a Basquiat? The solution to this dilemma was to send the work to a Freeport. A freeport is a secure storage facility where goods, like art, are exempt from customs duties, sales taxes, and Value Added Taxes. The work is untaxed because the artwork is considered to be “in transit.” Once delivery is “received,” taxes are paid. Let’s say the artwork has been in the freeport for years. In that period of time, the work appreciated 37% and it was then that the buyer decided to donate the Basquiat to the Getty. Did he have to pay taxes on it? No, the buyer did not. In fact, he was now legally allowed to take a 100% deduction on his taxes for donating to a non-profit. I like that idea, but this idea has a dark side, too.

The Art of the Wash: In or around 2014, one could walk into a Swiss art gallery, look at the gallerist or their assistant, and declare, “How much?” The Swiss gallerist or their assistant would reply, “Which piece?" The customer would reply, “ALL OF THEM.” Once the customer got the price, they would write a check for $500,000 and have the art sent to a Freeport, where it would be considered in-transit, untaxed and unseen, for years, again, till a delivery to a buyer was made. In the meantime, more likely than not, it would be sold back and forth to virtual people (read as shell companies), who only exist on paper. After all, in the United States, corporations are legally treated as a person or an organization, and a shell company is their P.O.Box.

The illicit funds were laundered through a process of layering that exploited the legal fiction of corporate personhood:

The Shell Game: The art was purchased and held by shell companies (the "virtual persons"), often in offshore havens. These entities, while having a legal right to transact, functioned solely as "P.O. Boxes" for the criminal's identity.

The String of Washes: The art became a pawn in a string of circular transactions between these virtual persons. The same work would be repeatedly bought and sold at artificially inflated prices (a form of pump and dump), and the money flow would be disguised as fabricated "consulting fees," "refunds," or "commissions" moving between the entities.

The Auction Exit: This mechanism allowed the criminal network to turn their illicit money into seemingly clean profit from an art investment, often finalized by a legitimate-looking auction house sale, thereby integrating the funds back into the clean global financial system.

The Correction: Why the Bubble Killed the Market: This corruption is a fundamental reason why legitimate, ethical galleries are now struggling. The money laundering bubble and the subsequent market correction have delivered a devastating one-two punch:

I. The Financial Contraction

The market distortion created a vacuum at the high end that could not sustain itself organically.

The Bubble Burst: The stratospheric valuations of the 2014-2018 era were based on the demand for a financial loophole, not artistic merit. The removal of a significant amount of this illicit capital due to legal enforcement has caused the high-end secondary market to contract sharply.

Reduced Liquidity: The clean-up has led to a significant decrease in transaction volume at the top, drying up liquidity for the entire ecosystem. Galleries that relied on even a trickle of that high-end money are now struggling with a buyer base that has literally vanished.

II. The Socio-Economic Collapse

This financial pressure collided with a fragile economy that has eroded the buyer base for the mid-level art market.

Unsustainable Overhead: Galleries are squeezed between the exorbitant commercial real estate rents and the high cost of art fair space rentals. These fixed costs are based on inflated, speculative market values, not the razor-thin margins of an ethical art business.

The Vanishing Middle Class: As income inequality has widened, the spending capacity of the core customer base has been decimated. The middle class is no longer able to support emerging artists. As I noted, the definition of luxury has shifted dramatically: owning an investment piece is unthinkable when simply owning a reliable used car is a financial struggle. The buyer pool for primary market art has merely collapsed.

The Obvious: These are the reasons given in the media, it is what the gallies think has happened, and the analysts. However, the cold, hard truth is that millions and millions of dollars have been removed from the market and the middle class.

III. The Legal Reckoning

The saving grace for the market's long-term integrity is that this systemic corruption has been directly addressed by law. The old, low-risk schemes of 2014 are largely over:

Piercing the Veil: Global laws, notably the EU’s Anti-Money Laundering (AML) Directives, have forced the creation of Ultimate Beneficial Owner (UBO) registries. This action directly breaches the secrecy of the "P.O. Box" by mandating that the real human being behind every shell company be identified.

Ending Exclusion: Art dealers and Freeports are now deemed "obliged entities." They are legally required to perform Know Your Customer (KYC) checks, scrutinize the source of funds, and file Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) for suspicious transactions.

Conclusion: The Cost of Opacity: The art market’s struggles are not just an aesthetic matter; they are a direct lesson in financial morality. The years when art was allowed to function as an unregulated shadow bank for the global elite created a speculative bubble that severely distorted values and drove up the cost of doing business. While new laws are working to clean the financial arteries of the art world, the damage done to the legitimate mid-level galleries—the true cultural engine of the market—has been profound. The long correction is underway, but the cost of the art world's decade of silence and complicity is measured not in tax revenue, but in the number of brick-and-mortar galleries that are now closing their doors. Thus, we artists are all gallerists now.

Elon Musk’s Lawsuit Mentions “Nonprofit” 111 Times—But Never Explains How It Saves Humanity. /

Elon Musk’s Lawsuit Mentions “Nonprofit” 111 Times—But Never Explains How It Saves Humanity — Musk’s non-profit demand is a bait and switch.

Mr. Elon Musk sells himself as a visionary who will save humanity from extinction. This is not hyperbole; it is documented. [0] But before we even evaluate the substance of that claim, we must ask whether he has standing to make it. In his court filing, Musk uses the word "nonprofit" 111 times, yet fails to explain how reverting OpenAI to a nonprofit structure would save humanity, elevate the public interest, or mitigate AI’s risks. The legal brief offers no humanitarian roadmap, no governance proposal, and no evidence that Musk has the authority to dictate the trajectory of an organization he holds no equity in. It reads like a bait and switch — full of virtue-signaling, devoid of actionable virtue. Marc Toberoff, Musk’s attorney, invokes dramatic language throughout the 82-page filing — even calling the alleged betrayal “of Shakespearean proportions.” But what’s noticeably absent is a proper declaration of legal standing. Remarkably, the word “standing” appears only once in the entire filing, but it refers not to Musk’s legal right to sue but to his “professional standing” being damaged by alleged affiliation. Meanwhile, Toberoff uses the word “notwithstanding” thirteen times.

Background: In November 2024, Elon Musk’s lawyers went before a federal court with a demand to block OpenAI’s position to convert from a non-profit organization into a for-profit. Federal Justice Gonzalez Rogers denied Musk the injunction, calling it “extraordinary,” which is shorthand for “going beyond what is usual, regular, or customary.”

However, Elon Musk filed a lawsuit against OpenAI’s CEO Sam Altman in August 2024, and Justice Gonzalez Rogers will let the lawsuit go forward. The legal brief itself is 82 pages long and quite hyperbolic and dramatic. On page one, this gem appears:

“…Elon Musk’s case against Sam Altman and OpenAI is a textbook tale of altruism versus greed. Altman, in concert with other Defendants, intentionally courted and deceived Musk, preying on Musk’s humanitarian concern about the existential dangers posed by artificial intelligence…”

Pretty strong language from a lawyer representing someone who publicly “…supported, and reportedly influenced, the Trump administration’s move to shutter the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID),” the government’s primary humanitarian arm. USAID dispenses billions in aid to combat poverty, disease, and respond to crises globally. By early 2025, USAID’s headquarters was closed, its website taken offline, and its leadership placed on administrative leave after resisting DOGE’s efforts to access secure systems. (read that sentence again slowly) Musk labeled USAID in a “tweet” on his “X” platform a “criminal organization” and called for its termination. (No proof, no evidenced was proffered.)

Consequently Real World Damage is occurring: 10,000+ Deaths from USAID Collapse After cheering the dismantling of USAID [1], Musk’s rhetoric helped pave the way for devastation. A Boston University study by epidemiologist Brooke Nichols tracked over 10,000 deaths directly linked to the shutdown of USAID-backed healthcare programs. These actions were widely criticized by humanitarian officials and Democratic and Republican representatives in Congress. [1][2]

These are not theoretical harms. They are ongoing tragedies. Musk claims to save humanity — but the numbers say otherwise.

In the lawsuit brief, Toberoff accuses Altman and others of betraying Musk, claiming: “The perfidy and deceit are of Shakespearean proportions.” I dearly hope Mr. Altman’s attorney responded with a Shakespearean retort: “Me thinks The lady doth protest too much.”

On page 11, point 61, Toberoff writes: “…Musk has long been concerned by the grave threat these advanced systems pose to humanity, which he has repeatedly warned is likely the greatest existential threat we face today. These dangers include, without limitation (or exaggeration), completely replacing the human workforce, supercharging the spread of disinformation, malicious human impersonation, and the manipulation of political and military systems, ultimately leading to the extinction of humanity…” Point blank, one has to ask if Musk is demanding that Justice Gonzalez Rogers legislate from the bench and determine what OpenAI can produce, create, or replace. That’s the role of Congress and other government bodies, not the judiciary.

Bait & Switch: I believe this non-profit demand is misinformation and disinformation. This is not unusual for Elon Musk. As far as the spread of misinformation goes, Musk’s “X” platform, formerly known as Twitter, arguably has a monopoly on spreading it. Since 2021, users on X in countries like the U.S., Australia, and South Korea were able to flag tweets they believed to be misleading. Musk later rescinded this. [4] Researchers found that “grooming” narratives — linking the LGBTQ+ community to slurs like “pedophile” — had exploded, with 1.7 million such tweets logged by the Center for Countering Digital Hate. [5] And Russian disinformation campaigns, once curbed by labeling content from authoritarian states, were allowed to flourish after Musk removed those restrictions. [6]

These citations are from respected researchers. But here’s the paradox: Musk accuses OpenAI of spreading misinformation while simultaneously profiting from it. If Musk were truly concerned about humanity’s safety, why is his own AI firm, xAI (Grok), a for-profit subsidiary of X Corp — the very platform accused of enabling hate speech and foreign propaganda?

His goal: To stall OpenAI’s growth and scare off future investors. Instead of defending truth, Musk appears to be projecting that exact questionable behavior onto OpenAI. His lawsuit seems more about disrupting a rival than defending virtue. In my opinion, this is classic law-fare — delay, distract, and exhaust, and his case isn’t about oversight or nonprofit governance. It’s about control.

The Legal Coup de Grace: Musk’s case falters most on the issue of standing. In the 82-page brief, the word is only used once — to refer to Musk’s “professional standing,” not his legal right to sue. [9] This omission suggests that even his attorney couldn’t argue a proper basis for bringing the case.

Here is a potential death blow to Musk’s ambitions: If OpenAI’s for-profit arm is restructured as a Delaware Public Benefit Corporation (PBC), (as Musk’s own xAI is) Musk’s case may be legally dead on arrival:

Under Delaware law, non-shareholders have no standing to sue over a PBC’s internal decisions.

This is not a hypothetical. It’s corporate law. To bolster this point, a 2024 California appellate court ruled that even a director of a nonprofit public benefit corporation loses standing to sue if not re-elected during the lawsuit. [12]

Musk doesn’t hold equity in OpenAI. He has no contractual authority, agreements and arguably lacks any legal standing. I think this is an option “SPANK” this man-child out of court.

His Private Life Is a Mess: Grimes, the mother of three of Musk's children, accused him of isolating her from their children. [3]

Ashley St. Clair sued Musk for sole legal custody, citing harmful behavior. [4]

Justine Wilson, Musk's first wife, publicly criticized his manipulation and abandonment. [5]

His daughter, Vivian Jenna Wilson, legally changed her name to cut ties with him and condemned his views. [6]

At least three mothers and one daughter have publicly spoken out. What Musk promises to the world, he appears to have denied to his own family.

The Minnesota Deepfake Lawsuit & Taylor Swift:In April 2025, Musk filed a separate lawsuit — this time to strike down a Minnesota law that bans non-consensual AI-generated deepfakes. [10] He argued that banning these manipulations violated free speech.

Minnesota’s law prohibits AI deepfakes used in:

Pornography

Political deception

Commercial fraud

And it was carefully crafted to protect celebrities, actors, and citizens alike.

This came after Musk shared a doctored image of Taylor Swift wearing a fake “Swifties for Trump” T-shirt — which spread widely before being debunked. [11]

Conclusion: Elon Musk’s lawsuit mentions “nonprofit” 111 times and produced 000 suggestions, ideas, or programs, and never once explains how a non-profit status saves lives, protects democracy, or elevates human flourishing. His case rests on vibes — not legal standing, not facts, not ethics.

And in that void, we are left with one truth: People are dying because of this man.

[0] https://www.economist.com/business/2023/12/05/elon-musks-messiah-complex-may-bring-him-down

[1] https://x.com/elonmusk/status/1886102414194835755?lang=en

[2] https://www.bu.edu/articles/2025/mathematician-tracks-deaths-from-usaid-medicaid-cuts/

[7] https://counterhate.com/research/twitter-fails-to-act-on-twitter-blue-accounts-tweeting-hate/